Ahead of the normal schedule, and with dinosaurs, rusps and biomechanics!

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

The title of this post sounds like that of a proper scientific paper, doesn't it? Something out of the

'Journal of Astrobiological Biomechanics', I guess. It's time to look at rusps again. My big rusp painting is finished, and as it is meant as a double-page spread, it is large: 7200 by 2700 pixels. A spoiler is shown above showing a fragment of a rusp in the background of the painting. The fragment has been halved in size and its area represents just 2% of that of the entire painting. The painting is based on earlier sketches. For more on rusps, either visit the main Furaha site or look at these posts:

sketches,

anatomy,

predation,

concept paintings, etc.

The evolution of new Furahan animals gets more complicated with time. In

the beginning I just sketched a pleasing shape and started painting

right away. Now, I worry more whether the animal makes evolutionary, mechanical and ecological sense.

Well, up to a point; this is science fiction and supposed to be fun,

after all.

Here are some of the steps in rusp 'ontology': they started with some quick sketches, and then the slow evolution began: successive legs were offset medially and laterally to avoid legs bumping into one another, followed by an arrangement for their skeleton. Their fore and aft whips are long and held horizontally rather like the tails and necks of sauropods, and hence have a

similar system of internal trusses as compressive elements at the bottom and ligaments at the top to withstand tensile stress. The whip is held up passively by these forces, so avoiding the high cost of doing that with muscle force only. The last stage involved refining the head of the rusp, and in particular its snout, or 'rostrum'. In an earlier post this rusp species was called Mammoth Rusp /

Megacrambis, but now it is the Brontorusp /

Brontocrambis; yes, that means 'Thunder Caterpillar'! The Mammoth Rusp still had some intricate limbs functioning as additional feeding aids under its snout. I was not too certain of that arrangement, and my doubts were confirmed by comments on that post. So the Brontorusp no longer has these additional mouth parts. The thing is, now we have a massive animal with a large head. How does it feed itself?

The mouth of the rusp is in its head, which seems obvious but in speculative biology not many things are obvious. Also note that rusps are large herbivores: they need a lot of food and spend much of their time eating. Moving about is costly, so it would be best if they moved the least possible amount to get their food, which does not sound as if there is much room to save energy. Let's tackle that by considering the problem of getting an animal's mouth on vegetation; there appear to be four solutions to do so; rusps use the fourth, but we'll come to that. The first solution, always necessary as vegetation will not come to you, involves walking to the food source.

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Klein et al; Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs. Indiana University Press 2011 |

But once an animal arrives at its 'foraging station' a nice way to save energy is to keep most of the body motionless and to have a long neck allowing the head and mouth to move about independently of the gut. For very large animals, needing to feed all day, it pays to divide their anatomy in mouth and guts; the rest is just 'other bits'. Sauropod dinosaurs used that method, and the image above is from a study on how far sauropod mouths could reach, depending on neck length and leg length. The idea is that the neck can move in a horizontal plane 90 degrees to the right and the left, and in a vertical plane straight up and down. If the animal is lying on the ground the volume of space that it can reach is one quarter of a sphere. If the base of the neck is higher up, when the animal is standing, the volume increases. The authors assume that the bottom part of the volume then is cylindrical whereas I would assume that to be spherical as well, but never mind.

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk | |

| |

Swans and geese have very flexible necks and can probably reach every point within that envelope, but if an animal has a neck less flexible than a swan's, only part of the volume is accessible to the mouth. If this is the first time you realised that geese and sauropods might have long necks for a similar reason, good!

The image above shows an adapted 'forage volume' for a sauropod: the outer red sphere is the outer limit of where it can reach, and the inner blue sphere represents the inner limit, assuming that the neck is too stiff for the animal to reach a point closer to its body. The human ('Marlene') is just there to keep the sauropod in its proper place.

The third solution to get the mouth near food is to use an appendage to shovel food towards the mouth. The best example I can think of is the elephant's trunk, which greatly increases the elephant's reach. The erstwhile rusp mouth limbs were short and not at all good as harvester limbs, and I did not wish to elongate them tenfold; they are gone. I also did not wish to turn the whip into a grasping organ. Rusp whips are not built for that, although in a pickle they can probably be used to knock a branch off a tree. Instead, rusps use a fourth system which is really just a combination of the last two: they carry their mouths towards the food without moving the rest of the head. The 'mouth extender' is extensible and based on a mechanical linkage system. In itself this is certainly not a new idea:

Earth fish have such systems in abundance.

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

This image shows a schematic view of the rusp rostrum. Start with the red shape in the foreground: it consists of two V-shapes starting from a vertical axis. All places where elements meet are in fact joints. The pink axis shows that the whole ensemble can rotate, but it can do other things as well: if the two Vs rotate towards one another, the whole shape will become longer and narrower. At its right end, the shape ends in two points on a horizontal line. Now copy the shape, rotate it by 90 degrees, and you get the blue shape in the foreground. The two points where the red shape ends act as connection points for the blue shape. Once connected, some movements from the red shape are connected to the blue one, but not all, and that makes the rusp rostrum quite versatile. In the back you see how the rostrum is formed by stringing red and blue shapes together. In reality the trusses are not formed by straight bones, but by curved ones, so the section of the rostrum is circular rather than rhombic. The cylinder on the right attempts to show the outlines of the bones on a cylinder.

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

And this image shows an as yet unmentioned aspect of movement: if the two starting points are brought closer together, this changes the section of the rostrum as well as its length. The right one is extended, the middle one shortened, and the right one is in neutral position. I expect rusp rostra (yes, that's the plural) to be able to double in length.

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

But we need more flexibility, and that is achieved by rotating the shapes and using the angle between the Vs for additional control. The stylised skeleton in the back shows what can be achieved. So there we are: an extensible and steerable system to get rusp mouths where they would otherwise not reach.

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

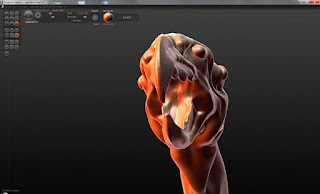

Here are two views of an adapted Sculptris model of a rusp head. I take it you will recognise the system of trusses under its hide.

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

And finally, a schematic rusp foraging volume, rather like that of the sauropod (the whip of this model is truncated). Note that the rusp can access a larger portion of the outer foraging volume than the sauropod. The volume itself is smaller though, as rusps are smaller than sauropods, and their rostra extend their reach, bot nearly as much as the sauropod's neck does. Marlene is standing in the forage volume, something I would definitely NOT recommend! In practice, rusps are ground feeders, not bothering about high branches. Have I told you about the ecology of the spotted plains where they live, where post of forests alternate with plains and how rusp feeding habits are to blame for that? No? Oh well, that is another story.