There are at least three clades of plants with different photosynthetic pigments on Furaha. While having leaves that are not green creates some 'otherworldliness', the shape of these plants is the one we know well: a stem with branches and leaves. At one time, some Furahan plants had enormous sail-like leaves. Unfortunately, reading about wind stresses on plants made me realise why Earth plants do not have sails or giant parasols for leaves. They are poor engineering, as giant leaves would suffer from wind damage (see here for what it takes to get large leaves). With some regret on my part, giant leaves followed ballonts (see here) on their way to the Forbidden Vault.

Even so, I always felt I should do more with plants and will share some ideas here. I find mangrove forests fascinating: plants, standing in salt seawater, form a barrier against waves and create their own ecosystem. Why are they limited to some tropical coats, and why aren't temperate coasts also blanketed with a whole range of different 'mangrovian' ecosystems? If Earth doesn't offer us such a spectacle, could Furaha have vast ribbon-like forests covering its coastlines? That's something I haven't worked out yet; I should probably first understand why this does not happen on Earth. So far, I suspect that the origin of Earth's land plants, stemming from freshwater organisms, has something to do with it, which begs the question how mangroves manage salt water. I will have to study that, but for this post I am more interested in how they withstand waves.

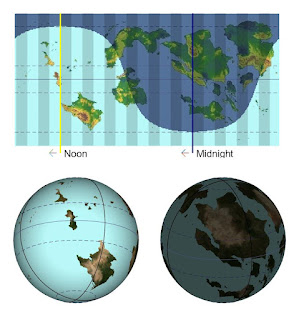

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

|

| Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk |

Another plant aspect I once came up with was a desert ecosystem in which the local plants really went out of their way to fend off herbivores. Some plants produced caltrops, also known as crow's foot, among other names. Caltrops are the unpleasant pointy bits of iron strewn on the ground to make life difficult for the enemy's men and horses. In the case of Furahan caltrop plants, the spikes grew upward from the roots of some trees and shrubs.

|

| Click to enlarge; from Wikipedia |

Those Furahan root spikes looked -intentionally- like the top left caltrop in the image above, dating from 1505.

Other shrubs had nasty strong and very sharp thorns. Still, some herbivores, like the animal shown lying in the shade in the picture above, developed a string and tough carapax allowing them to move through the nasty shrubbery. The image is from an old oil painting that I later decided did not work well, so it was delegated to the Forgotten Attic.

But one plant species isn't on the painting. What if thorns that constantly touched a branch of the same plant would bend around that branch, clasping it firmly? If that would happen on many branches, the result would be a strong structure, one in which branches could not simply be pushed aside. This weblike structure would make life more difficult for herbivores, putting most of the plant outside their reach (well, until they evolved long tongues or the equivalent of pruning shears, of course).

|

| Click to enlarge; from Wikipedia |

Another way to reach this webbed structure involves 'inosculation'. That isn't a concept I came up with for fun, but an existing word: here is the Wikipedia page on inosculation. According to Wikipedia, when tree trunks or roots rub against one another, the bark may wear off and the cambium, the live growing tissue of a tree, of the two touching parts may fuse and grow on from there, ultimately producing new bark around the touching area. This explanation centres on damage to the bark exposing the cambium. Grafting, the artificial variant of inosculation, also relies on would healing.

Tree roots can certainly fuse, but roots do not move much, so I find it hard to believe that root inosculation must start with damage due to rubbing. This suggests that mere touch or pressure without movement seems sufficient to start inosculation. But roots and trunks can also press against stone, and such pressure does not seem to abrade the bark at all. In the end, it is often the stone that moves instead! Do trees recognise that they are touched by another part of themselves, and then allow or even favour inosculation? I found some evidence that some plants, like English ivy and strangler figs, readily from natural stem grafts (in this free paper). You can imagine that a climbing plant might benefit from a web structure.

|

| Click to enlarge; from Wikipedia |

A strangler fig needs to be able to stand on its own stems when its victim dies, and firm connections between the stems are then quite beneficial. The image above, from the Wikipedia page on strangler figs, shows this fusion tendency quite clearly (but the page does not mention this).

That paper led to another stating that roots indeed graft naturally (here). One explanation for this tendency was that connected roots provide better anchorage (for other explanations, read the paper).

Well, well. It seems that some Earth plants indeed readily 'inosculate' to obtain a mechanical advantage! That is what I wanted, and as usual every time you think you had an original idea for a Speculative Biology project has already been tried by 'Nonspeculative Biology'...

All this makes me think that Furahan plants could do with more self-inosculation. The resulting cross-struts offer mechanical advantages that might help Furahan mangrovian plants to withstand the force of waves. In deserts, I can see plants preventing access to herbivores too.

-------------------------

For other posts on alien plants, start here or just search the blog for 'alien plants'. And for other posts of defunct paintings, start here.

-----------------------

This is post #300! I also forgot to mention that the blog passed its 16th birthday in April, and that the 300 posts amassed a total of about 2680 comments.