The Epona Project was, or perhaps is, probably the first serious attempt to build an fictional biosphere from scratch. There is still a website, definitely worth watching. Admittedly, the project has stopped in the sense that no new life forms have been developed for a long time, nor is that likely to happen. But the website is being added to, and I return to it from time to time. The last blog entry on Epona is to be found here, while another one that shows the same scene as is shown in the film below is right here. This time, I used Vue Infinite (version 7.5) to produce a film of almost one minute duration.

How does this work? Well, first of all, there were the life forms to consider. Steven Hanly had modelled them in the past, and it proved possible to port some of his models into the Vue environment. The 'uther' you see flying in the scene is entirely Stephen's doing. The plants could not be used directly, as present-day computer imagery requires more detail than was available when he first designed the models. They were therefore designed anew, using XFrog for the large leaves of the pagoda trees and for all small plants. The stems of the large pagoda tress were done in Vue Infinite. The trees were assembled in Vue, and Vue's 'ecosystem' feature was used to create a terrain with a stream running through it. Then just imagine that a 5-second fragment of film may need some 34 hours to render.

After that, a bit of sound was added, a process I have hardly any experience with. I hope the result is not too jarring.

Anyway, there we are: perhaps the film is about a robot drone taking a look on an Eponan archipelago, covered by a pagoda forest. There is a larger version on YouTube. The original film on my computer is much better; I wish I knew more about optimising quality while compressing a video...

Showing posts with label Epona Project. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Epona Project. Show all posts

Saturday, 23 October 2010

Sunday, 3 January 2010

Anatomy of an alien III: Europan waters

The first blog entry in this new decade travels back in time again, to the 1997 BBC television series 'Anatomy of an alien'. This time the chosen fragment chosen deals with life on the moon Europa, or perhaps it may be better to call it 'in Europa', as the life forms in question are found in water underneath an ice cap over 15 km thick (according to the documentary).

You will first see an explanation of deep ocean vents on Earth, and those are never boring. Jack Cohen makes an appearance again, to speculate about similar vents in Europan seas or lakes. The vents are surrounded with walls built by bacteria that stretch upwards to form very long tubes. The speculation really gets underway when it deals with the ecosystem surrounding these tubes. There are creatures that can bite or drill through the wall of the tube, after which they gorge themselves on bacteria from within the tube. Of course there are predators out there too, preying on the 'grazers'.

Here is a picture of a bacterivore; the predators have almost exactly the same shape. There is a feeding trunk on the front end of the animal, underneath the central opening. There is another opening in the front end of the animal; what is it for? Unfortunately, the documentary keeps completely silent about the body plan of these animals, which is a pity.

There is an opening right at the front, and one at the back. The one in the front is not for feeding. Perhaps these are the inlet and outlet openings of its respiratory system. After all, there is no reason to have air go in and out through the same opening, as is the case in Earth's tetrapods. Actually, using the same opening for air moving in and out is not good engineering, and is probably just a remnant of lungs starting as a sac with just one opening. In Earth's fish, waters enter the mouth and leave through its sides after having passed through the gills; a much better design! Obviously, evolution should be able to find other solutions on other worlds: air enters the lungs of Furahan hexapods through openings at the front of the trunk, and exits the body at its rear end (not that you can see that on any of the paintings on the site, but is true nevertheless).

Then again, the Europan bacteriovore's openings might have to do with propulsion, in which case these animals would have the same propulsion system as is found on Furaha. Just visit the page, choose the 'water' icon; choose 'swimming with...', and then got to the 'tubes' page. There you are. To save you the trouble I copied the image to this blog message; mind you, the image shows the external appearance of the animal; to understand how it works you still have to visit the page. I doubt that this propulsion system was separately invented for the Europan creatures. If so much thought would have gone into their design, you would think that this neat feature would be mentioned, and it isn't.

Still, there is something else about their propulsion that makes me wonder. The animals have a set of three fins around their body, more or less like the pectoral and back fins of sharks and dolphins. This makes sense, as three such fins are useful in countering rotations around the body's front-to-aft axis. You would want such fins near the centre of the body, as they would impede movements around the other axes if placed at the front or the rear of the animal. These animals indeed have three such wings right where you would expect them, around the centre of mass. As an aside, you may well wonder why there are three. To counter rotations, two or four (or more) would work just as well. Their area may have to increase if you have fewer fins, and vice versa, but that does not seem to be an important factor. Some whales have large dorsal fins and some have no dorsal fins at all, so having two seems to work as well as having three. Why are there never four? Is this just an evolutionary accident? Perhaps it is easier to have more such fins at the bottom half of the animal than at the top half, if only to make it easier to keep the body upright.

Anyway, now have a look at the tail of Europan bacterivores: there is another, smaller, set of three fins. That only makes sense if the animal needs more to be kept on track like an arrow, but this 'triad' fin design is not optimal if you use the tail for propulsion. Suppose you wish to beat the tail in an up and down direction: with a triad set the top fin will be useless for propulsion. While moving upwards it might even start to bend sideways and then it would impair propulsion. The other two will not be perpendicular to the direction of movement and will therefore not provide optimal thrust. No, if you want a beating tail, the surfaces providing propulsion must be perpendicular to the direction of the beat, and surfaces not aiding in propulsion should not be in the way.

The tails of sharks and whales provide excellent examples of this design. The pictures above were taken from the internet. The whale shark beats its tail sideways, and the 'stem' of the tail, just before the tail fin, is flattened sideways. In this way, there is room for the attachment of muscles and ligaments without impairing propulsion. The two photographs of orca's show that an orca's tail stem is flattened vertically, exactly as expected for an animal that beats its tail up and down.

Back to Europan bacterivores. Their tails suggest a mode of propulsion similar or identical to the ones I invented for Furaha. Convergent speculation once again? Possibly; remember that this type of propulsion results in linear motion without any externally visible means of propulsion. That is not what you see in the video. Instead, the predators near the end can be seen to swim with a strongly undulatory pattern, like the one you would expect for animals with sideways-beating tails.

I wonder what happened to cause this odd combination of a design plan with a movement pattern that doesn't seem to fit the plan. The people who designed these animals knew what they were doing, so the answer probably does not lie there. Perhaps the animators simply added a familiar type of movement to add some spice to the footage? That is possible: I remember from conversations with Steven Hanly that the movement of Eponan uthers in the same documentary did not come out as planned either. I doubt we will ever know.

You will first see an explanation of deep ocean vents on Earth, and those are never boring. Jack Cohen makes an appearance again, to speculate about similar vents in Europan seas or lakes. The vents are surrounded with walls built by bacteria that stretch upwards to form very long tubes. The speculation really gets underway when it deals with the ecosystem surrounding these tubes. There are creatures that can bite or drill through the wall of the tube, after which they gorge themselves on bacteria from within the tube. Of course there are predators out there too, preying on the 'grazers'.

Click to enlarge; copyright BBC

Here is a picture of a bacterivore; the predators have almost exactly the same shape. There is a feeding trunk on the front end of the animal, underneath the central opening. There is another opening in the front end of the animal; what is it for? Unfortunately, the documentary keeps completely silent about the body plan of these animals, which is a pity.

There is an opening right at the front, and one at the back. The one in the front is not for feeding. Perhaps these are the inlet and outlet openings of its respiratory system. After all, there is no reason to have air go in and out through the same opening, as is the case in Earth's tetrapods. Actually, using the same opening for air moving in and out is not good engineering, and is probably just a remnant of lungs starting as a sac with just one opening. In Earth's fish, waters enter the mouth and leave through its sides after having passed through the gills; a much better design! Obviously, evolution should be able to find other solutions on other worlds: air enters the lungs of Furahan hexapods through openings at the front of the trunk, and exits the body at its rear end (not that you can see that on any of the paintings on the site, but is true nevertheless).

Click to enlarge; copyright Gert van Dijk

Still, there is something else about their propulsion that makes me wonder. The animals have a set of three fins around their body, more or less like the pectoral and back fins of sharks and dolphins. This makes sense, as three such fins are useful in countering rotations around the body's front-to-aft axis. You would want such fins near the centre of the body, as they would impede movements around the other axes if placed at the front or the rear of the animal. These animals indeed have three such wings right where you would expect them, around the centre of mass. As an aside, you may well wonder why there are three. To counter rotations, two or four (or more) would work just as well. Their area may have to increase if you have fewer fins, and vice versa, but that does not seem to be an important factor. Some whales have large dorsal fins and some have no dorsal fins at all, so having two seems to work as well as having three. Why are there never four? Is this just an evolutionary accident? Perhaps it is easier to have more such fins at the bottom half of the animal than at the top half, if only to make it easier to keep the body upright.

Anyway, now have a look at the tail of Europan bacterivores: there is another, smaller, set of three fins. That only makes sense if the animal needs more to be kept on track like an arrow, but this 'triad' fin design is not optimal if you use the tail for propulsion. Suppose you wish to beat the tail in an up and down direction: with a triad set the top fin will be useless for propulsion. While moving upwards it might even start to bend sideways and then it would impair propulsion. The other two will not be perpendicular to the direction of movement and will therefore not provide optimal thrust. No, if you want a beating tail, the surfaces providing propulsion must be perpendicular to the direction of the beat, and surfaces not aiding in propulsion should not be in the way.

Whale shark / orca / orca; click to enlarge

The tails of sharks and whales provide excellent examples of this design. The pictures above were taken from the internet. The whale shark beats its tail sideways, and the 'stem' of the tail, just before the tail fin, is flattened sideways. In this way, there is room for the attachment of muscles and ligaments without impairing propulsion. The two photographs of orca's show that an orca's tail stem is flattened vertically, exactly as expected for an animal that beats its tail up and down.

Back to Europan bacterivores. Their tails suggest a mode of propulsion similar or identical to the ones I invented for Furaha. Convergent speculation once again? Possibly; remember that this type of propulsion results in linear motion without any externally visible means of propulsion. That is not what you see in the video. Instead, the predators near the end can be seen to swim with a strongly undulatory pattern, like the one you would expect for animals with sideways-beating tails.

I wonder what happened to cause this odd combination of a design plan with a movement pattern that doesn't seem to fit the plan. The people who designed these animals knew what they were doing, so the answer probably does not lie there. Perhaps the animators simply added a familiar type of movement to add some spice to the footage? That is possible: I remember from conversations with Steven Hanly that the movement of Eponan uthers in the same documentary did not come out as planned either. I doubt we will ever know.

Sunday, 13 December 2009

Springcroc in springtime (Epona IV)

The springcroc is not a Furahan but an Eponan animal. Parts of the vast Epona material have reappeared on the web, and the many life forms discussed there include the springcroc. You will find it right here. Regular followers of this blog will now that I have discussed it before (first here, and then here and afterwards here), and I will probably come back to it in the future (I was one of the people who used to work on it, so that's why).

The thing to remember about Eponan terrestrial life forms is that they left the sea fairly recently, so adaptations to a land-based existence have not yet reached optimal solutions yet. That holds for Eponan trees, whose stems have not yet evolved anything as suitable as wood, and it may also hold for the springcroc. Its general design is very nice: in essence a springcroc is just a large stomach enclosed by two half shells. It lies in waiting in some swamp, and when a suitable prey arrives in striking distance the springcroc catapults itself towards the prey using its own froglike leg. The prey is engulfed by the stomach and is slowly digested. Simple, but simple solutions work.

This is the springcroc as shown on the Epona site. Steven Hanly, one of the people involved in the Epona project, produced many 3D Epona images at the time, many of which can be seen on his web page. For this purpose he had also built a 3D springcroc computer model. A few months ago he sent me his 'obj' file to have a look at. I was also trying out ZBrush, a 3D 'sculpting' program that is extremely well-suited to produce organic looking animal shapes. I imported the springcroc shape, and used it to try out some embellishments, as ZBrush allows you to push and pull at objects at will. As you will see this ability is the reason why the poor animal now has so many bumps on its head.

I also decided to 'bodybuild' its musculature somewhat. With just one leg it must be difficult for the springcroc to control the direction of its jump in a lateral direction. While a jump in the general direction of the prey can work for extremely slow prey animals, a jump with some more precision should help the springcroc to rise to the pinnacle of the food chain (or at least to stay in plaavce with more ease). The only way the springcroc can exert lateral control is by pushing harder or less hard on either of its two toes while jumping, so these are fairly wide apart. For similar reasons the joints between the segments of its leg were broadened: to provide more joint stability as well as a bit more control.

So here it is: a springcroc before and after embellishment in ZBrush. As said, the bumps serve mainly to make it look more interesting.

Having done that, I exported the model again, and after some trouble loaded it into Vue Infinite, where I embedded it in a meadow-like environment of Eponan plant (well, actually one plant was designed for Furaha, but these images are sketches, nothing more). The springcroc should really be coloured a bit more interestingly, but this is just a work in progress. The white leaves reminded me of springtime, so there you have it: a springcroc in springtime...

The thing to remember about Eponan terrestrial life forms is that they left the sea fairly recently, so adaptations to a land-based existence have not yet reached optimal solutions yet. That holds for Eponan trees, whose stems have not yet evolved anything as suitable as wood, and it may also hold for the springcroc. Its general design is very nice: in essence a springcroc is just a large stomach enclosed by two half shells. It lies in waiting in some swamp, and when a suitable prey arrives in striking distance the springcroc catapults itself towards the prey using its own froglike leg. The prey is engulfed by the stomach and is slowly digested. Simple, but simple solutions work.

This is the springcroc as shown on the Epona site. Steven Hanly, one of the people involved in the Epona project, produced many 3D Epona images at the time, many of which can be seen on his web page. For this purpose he had also built a 3D springcroc computer model. A few months ago he sent me his 'obj' file to have a look at. I was also trying out ZBrush, a 3D 'sculpting' program that is extremely well-suited to produce organic looking animal shapes. I imported the springcroc shape, and used it to try out some embellishments, as ZBrush allows you to push and pull at objects at will. As you will see this ability is the reason why the poor animal now has so many bumps on its head.

I also decided to 'bodybuild' its musculature somewhat. With just one leg it must be difficult for the springcroc to control the direction of its jump in a lateral direction. While a jump in the general direction of the prey can work for extremely slow prey animals, a jump with some more precision should help the springcroc to rise to the pinnacle of the food chain (or at least to stay in plaavce with more ease). The only way the springcroc can exert lateral control is by pushing harder or less hard on either of its two toes while jumping, so these are fairly wide apart. For similar reasons the joints between the segments of its leg were broadened: to provide more joint stability as well as a bit more control.

So here it is: a springcroc before and after embellishment in ZBrush. As said, the bumps serve mainly to make it look more interesting.

Having done that, I exported the model again, and after some trouble loaded it into Vue Infinite, where I embedded it in a meadow-like environment of Eponan plant (well, actually one plant was designed for Furaha, but these images are sketches, nothing more). The springcroc should really be coloured a bit more interestingly, but this is just a work in progress. The white leaves reminded me of springtime, so there you have it: a springcroc in springtime...

Saturday, 11 July 2009

Mechanical and biological flight: heavier than air

While trying to find mechanical analogues for tetropters I stumbled upon some other technological innovations that might be transported to alien worlds as biological means of achieving flight. Some deal with heavier-than air flight, others with lighter than air. Let's start with the heavier than air designs, and leave the ballonts-like designs for another time.

On Earth, no animal has separate mechanisms for thrust and lift; instead, wings, and especially wing control, are subtle enough to combine thrust with lift. This holds for birds, bats, pterosaurs and insects, and of all these insect flight is in some aspects the most advanced, as insects can hover as well as fly forwards. Among vertebrates only hummingbirds are known to have evolved this ability. I suppose that this dual thrust-and-lift role is a typical example of biology performing much better than human creativity, and would not be surprised that advanced neural control is responsible for this superiority. But let us assume that separating thrust and lift can also work in the animal realm. In fact, I dreamed up such an animal once: the very first one I ever did on Furaha, in fact, Here it is: it has never before been shown on the site, and it is only a fragment of a larger painting.

Its scientific name is 'Propulsor mechanicus', and I have forgotten its common name (a 'zummer'?). What you can see is that its front pair of wings does not flap, but the hind pair flaps very energetically, and provides thrust on the upstroke as well as the down stroke of the wings. As such, these wings are very much like an insects' wings in hovering flight, but rotated 90 degrees so the thrust is directed backwards instead of downwards.

Mechanical flying machines nearly always have a separation of thrust and lift, and most thrust mechanisms cannot be used as an inspiration for animal flight, as there are rotary parts involved. But people have been trying to design working 'ornithopters' for ages, and some of these are interesting.

For instance, the video above show a design wing a large lifting immobile wing, and two hind wings that provide thrust. The source is here. The two hind wings flap up and down rather like the fluked tail of a whale, but where a whale has only one tail, this design uses two such tails, one above the other. According to the text they flap in counter phase to provide balance. The design reminded me a bit of the Uther design for the Epona Project, if I understood correctly how Uthers were supposed to move: Steven Hanly once told me that the animation shown on the BBC documentary that you can find in an earlier post was not at all what he had in mind.

Uthers, one of which is shown here, have a large unpaired hind wing, and I think it provides the thrust while the paired front wings provide lift (Steven, please jump in if I got this wrong!).

If we leave the separation of thrust and lift behind, we can move on to more typical biological flight, in which each wings has both functions. But even then there are some interesting machines to be found. The typical body plan of a Furahan 'avian' involves a tetrapterate design with two paired wings. Some of you may have noticed that the first pair may overlap the second pair slightly, but in others, the two pairs are placed very far apart. he two images that follow illustrate the two variants.

The idea behind the overlapping design was taken from sailing boats, in which sails that partially overlap work together to improve the boat's ability to make use of the wind. In aircraft 'canard' wings function similarly. I thought the same could be done with animal wings, hence the design. The other design also seemed fairly straightforward to me, in that the two pairs of wings allow great flexibility in how they are used: in unison or separately. I found ornithopter designs that I had never considered though, in which the two wings of one pair do not move up or down together, but instead one moves up while the other moves down. I do not think I like it, as this movement would cause asymmetrical stresses that seem impractical. Do not expect any Furahan animals to use this mode of flight. Still, people have built designs along such lines, and here is one:

This copy was taken from YouTube, but a much better quality can be seen on this page on the 'Entomopter' , which also shows a variant designed to fly on the planet Mars...

I will end with a design that I had not thought about and that I do find appealing. Take a tetrapterate avian like the bulchouk above, and move the first pair of wings even further aft so the two pairs are above one another. My first thought is that they would be in one another's ways, and they would. Still, if one pair moves up while the other moves down, you get a 'clap' effect, and those appear advantageous. In one of the previous posts on tetropters and micro air vehicles, two designs use exactly this type of wing plan: the Delfly and a Japanese design. Have a look again here; perhaps that is a design that one day will take to the skies as a fictional avian.

On Earth, no animal has separate mechanisms for thrust and lift; instead, wings, and especially wing control, are subtle enough to combine thrust with lift. This holds for birds, bats, pterosaurs and insects, and of all these insect flight is in some aspects the most advanced, as insects can hover as well as fly forwards. Among vertebrates only hummingbirds are known to have evolved this ability. I suppose that this dual thrust-and-lift role is a typical example of biology performing much better than human creativity, and would not be surprised that advanced neural control is responsible for this superiority. But let us assume that separating thrust and lift can also work in the animal realm. In fact, I dreamed up such an animal once: the very first one I ever did on Furaha, in fact, Here it is: it has never before been shown on the site, and it is only a fragment of a larger painting.

Its scientific name is 'Propulsor mechanicus', and I have forgotten its common name (a 'zummer'?). What you can see is that its front pair of wings does not flap, but the hind pair flaps very energetically, and provides thrust on the upstroke as well as the down stroke of the wings. As such, these wings are very much like an insects' wings in hovering flight, but rotated 90 degrees so the thrust is directed backwards instead of downwards.

Mechanical flying machines nearly always have a separation of thrust and lift, and most thrust mechanisms cannot be used as an inspiration for animal flight, as there are rotary parts involved. But people have been trying to design working 'ornithopters' for ages, and some of these are interesting.

For instance, the video above show a design wing a large lifting immobile wing, and two hind wings that provide thrust. The source is here. The two hind wings flap up and down rather like the fluked tail of a whale, but where a whale has only one tail, this design uses two such tails, one above the other. According to the text they flap in counter phase to provide balance. The design reminded me a bit of the Uther design for the Epona Project, if I understood correctly how Uthers were supposed to move: Steven Hanly once told me that the animation shown on the BBC documentary that you can find in an earlier post was not at all what he had in mind.

Uthers, one of which is shown here, have a large unpaired hind wing, and I think it provides the thrust while the paired front wings provide lift (Steven, please jump in if I got this wrong!).

If we leave the separation of thrust and lift behind, we can move on to more typical biological flight, in which each wings has both functions. But even then there are some interesting machines to be found. The typical body plan of a Furahan 'avian' involves a tetrapterate design with two paired wings. Some of you may have noticed that the first pair may overlap the second pair slightly, but in others, the two pairs are placed very far apart. he two images that follow illustrate the two variants.

The idea behind the overlapping design was taken from sailing boats, in which sails that partially overlap work together to improve the boat's ability to make use of the wind. In aircraft 'canard' wings function similarly. I thought the same could be done with animal wings, hence the design. The other design also seemed fairly straightforward to me, in that the two pairs of wings allow great flexibility in how they are used: in unison or separately. I found ornithopter designs that I had never considered though, in which the two wings of one pair do not move up or down together, but instead one moves up while the other moves down. I do not think I like it, as this movement would cause asymmetrical stresses that seem impractical. Do not expect any Furahan animals to use this mode of flight. Still, people have built designs along such lines, and here is one:

This copy was taken from YouTube, but a much better quality can be seen on this page on the 'Entomopter' , which also shows a variant designed to fly on the planet Mars...

I will end with a design that I had not thought about and that I do find appealing. Take a tetrapterate avian like the bulchouk above, and move the first pair of wings even further aft so the two pairs are above one another. My first thought is that they would be in one another's ways, and they would. Still, if one pair moves up while the other moves down, you get a 'clap' effect, and those appear advantageous. In one of the previous posts on tetropters and micro air vehicles, two designs use exactly this type of wing plan: the Delfly and a Japanese design. Have a look again here; perhaps that is a design that one day will take to the skies as a fictional avian.

Sunday, 10 May 2009

The Epona Project III

Something is happening with Epona, and it is good. When I first referred to the Epona Project several weeks ago the website still shows signs of damage from a malevolent attack, but those had been repaired the second time, and some new content had been added. This time, I am happy to say, the website has received a makeover, and it looks excellent.

The site discusses how Epona was conceived and how its biological inhabitants evolved, starting with the geological constraints put in place at the beginning of the process. The process in question -' speculative creation'- is how the participants came up with specific life forms and body plans. I have no desire to become entangled in fruitless discussions regarding deity-driven creation, but what other word than creation can be used to describe it?

The genesis of such a world (couldn't resist that...) obviously evokes a comparison with biological evolution, and that comparison is more or less apt. From own experience I know that a specific body plan, one conceived, can quickly be taken for granted and can then be viewed as a 'starter set' to develop new forms. Both the animals and plants on Epona seem to have gone through the same process of explosive radiation. The likeness with biological evolution would be greater if species did not only appear on the scene, but would also die out. Were some ideas rejected during the conventions, and were some body designs scoffed at? Are these still to be found somewhere in an Eponan Burgess shale buried under limestone: extinct now but once, shortly, present?

But that is not today's main course. In 1997 the BBC did a series apparently called 'A weekend on Mars', and one program in that series was called 'Natural history of an alien'. It showed a range of fictional planets with their life forms, ranging from Aldiss' Helliconia to, you guessed it, Epona. There were almost four minutes devoted to Epona, and I have taken the liberty of showing that section here. I do not think that the program itself is available for sale anywhere, or at least I have not been able to find any mention of that. There are listings of it in Wikipedia, and it can be found in the Internet Movie Database, but I found no mention of a DVD or, more appropriate for 1997, a video. I did find some references that the program was aired in the USA in 1998, possibly by the Discovery Channel under the name 'Anatomy of an alien'. The Discovery Channel's website only came up with 'Alien Planet', something completely different.

So here it is. The Epona Project 12 years ago.

The site discusses how Epona was conceived and how its biological inhabitants evolved, starting with the geological constraints put in place at the beginning of the process. The process in question -' speculative creation'- is how the participants came up with specific life forms and body plans. I have no desire to become entangled in fruitless discussions regarding deity-driven creation, but what other word than creation can be used to describe it?

The genesis of such a world (couldn't resist that...) obviously evokes a comparison with biological evolution, and that comparison is more or less apt. From own experience I know that a specific body plan, one conceived, can quickly be taken for granted and can then be viewed as a 'starter set' to develop new forms. Both the animals and plants on Epona seem to have gone through the same process of explosive radiation. The likeness with biological evolution would be greater if species did not only appear on the scene, but would also die out. Were some ideas rejected during the conventions, and were some body designs scoffed at? Are these still to be found somewhere in an Eponan Burgess shale buried under limestone: extinct now but once, shortly, present?

But that is not today's main course. In 1997 the BBC did a series apparently called 'A weekend on Mars', and one program in that series was called 'Natural history of an alien'. It showed a range of fictional planets with their life forms, ranging from Aldiss' Helliconia to, you guessed it, Epona. There were almost four minutes devoted to Epona, and I have taken the liberty of showing that section here. I do not think that the program itself is available for sale anywhere, or at least I have not been able to find any mention of that. There are listings of it in Wikipedia, and it can be found in the Internet Movie Database, but I found no mention of a DVD or, more appropriate for 1997, a video. I did find some references that the program was aired in the USA in 1998, possibly by the Discovery Channel under the name 'Anatomy of an alien'. The Discovery Channel's website only came up with 'Alien Planet', something completely different.

So here it is. The Epona Project 12 years ago.

Sunday, 26 April 2009

Epona II

I discussed the Epona project in this blog recently, and stated that it was at its time the biggest and best-developed world of fictional biology. Here is a surprise; it might very well still be the biggest such project! The problem is that most of it was only visible to the few people taking care of the project, among whom Greg Barr was one the people holding it all together. The website never showed more than the beginning of he project, and did not even discuss the major life forms and their physiology. The good news is that part of the old website has now been restored (it was damaged by a virus or a hacker). So take a look there, and let's hope that more of the wealth of Epona data will yet appear for all to see.

Meanwhile, I can discuss a few glimpses. There is a Kingdom Myoskeleta. These organisms do not have a sketelon, neither on the inside nor on the outside. What they have is a set of extensile muscles without joints. That is right, extensile muscles, not contractile ones. There were no bones, hence no joints. By expanding on a specific site in a thick muscle rod, the rod could bend, stretch or spiral in any shape desired. This was no mean feat; the limbs of any creature with such extensile muscles acted a bit like tentacles. I remember writing a critique on these muscles along the same lines as later reappeared in this blog: there were four blog entries called 'Why there is no walking with tentacles': one, two, three and four. If you read them, you will find that I made a case for the development of joints in any limb destined for serious weight bearing. I think that the arguments hold for tentacles of any type, with contractile or extensile muscles. By the way, I thought that extensile muscles could perhaps be made to work in a roundabout manner, but that is perhaps something for another day.

The myoskelata basically consist of a barrel with a set of limbs at either end. There are five of these limbs, and in principle they branch into three 'fingers'. Here is such a basic organism:

The Myoskeleta are divided into two phyla: the Myophyta, plants for all practical purposes (the other phylum is the Pentapoda; they're animals). Take the basic shape, drop one end into the ground to act as roots, and span a membrane between the five limbs: that is a basic Pagoda Tree. If you add a similar layer ('tier') on top of it, you understand the tiered appearance of a pagoda forest. You will be able to recognise this fivefold symmetry for most of the plants shown on the cover of the recent book on how to grow Eponan plants (see the Hades Publishing page on the Furaha website).

In principle these 'trees' can still move a bit, for instance to direct their leaves towards the sun. Intriguing, aren't they? I will add a few images of such Eponan forests. They are in development together with Steven Hanly.

Ah yes, I showed an image of a flying animal in the previous post. It was modeled by Steven, and is a pentapod, meaning its basic anatomy is similar to that of the trees it flies over. The species is a Uther, and it is intelligent. Life on Epona has developed intelligence, unlike Furaha (and the reason why there are no 'sophonts' on Furaha deserves mention on its own, one day).

Meanwhile, I can discuss a few glimpses. There is a Kingdom Myoskeleta. These organisms do not have a sketelon, neither on the inside nor on the outside. What they have is a set of extensile muscles without joints. That is right, extensile muscles, not contractile ones. There were no bones, hence no joints. By expanding on a specific site in a thick muscle rod, the rod could bend, stretch or spiral in any shape desired. This was no mean feat; the limbs of any creature with such extensile muscles acted a bit like tentacles. I remember writing a critique on these muscles along the same lines as later reappeared in this blog: there were four blog entries called 'Why there is no walking with tentacles': one, two, three and four. If you read them, you will find that I made a case for the development of joints in any limb destined for serious weight bearing. I think that the arguments hold for tentacles of any type, with contractile or extensile muscles. By the way, I thought that extensile muscles could perhaps be made to work in a roundabout manner, but that is perhaps something for another day.

The myoskelata basically consist of a barrel with a set of limbs at either end. There are five of these limbs, and in principle they branch into three 'fingers'. Here is such a basic organism:

The Myoskeleta are divided into two phyla: the Myophyta, plants for all practical purposes (the other phylum is the Pentapoda; they're animals). Take the basic shape, drop one end into the ground to act as roots, and span a membrane between the five limbs: that is a basic Pagoda Tree. If you add a similar layer ('tier') on top of it, you understand the tiered appearance of a pagoda forest. You will be able to recognise this fivefold symmetry for most of the plants shown on the cover of the recent book on how to grow Eponan plants (see the Hades Publishing page on the Furaha website).

In principle these 'trees' can still move a bit, for instance to direct their leaves towards the sun. Intriguing, aren't they? I will add a few images of such Eponan forests. They are in development together with Steven Hanly.

Ah yes, I showed an image of a flying animal in the previous post. It was modeled by Steven, and is a pentapod, meaning its basic anatomy is similar to that of the trees it flies over. The species is a Uther, and it is intelligent. Life on Epona has developed intelligence, unlike Furaha (and the reason why there are no 'sophonts' on Furaha deserves mention on its own, one day).

Sunday, 19 April 2009

One year on

I started this blog on April 22, 2008, or almost a year ago. Has it been a success? Hard to tell, really. How do you judge the success of a blog? by the number of readers? In that case I should probably write about religion, politics and sex, preferably in combination. That suggests it might be more to the point to ask how you judge success of a blog devoted to speculative biology from the viewpoint of one person's particular take on the subject? You can't; suffice it to say that so far I like the number of visitors, which is growing, and like writing entries.

There were 39 entries in one year, not counting this one. Not exactly once a week, but not bad, I think. On May 19 last year I made a list of things I needed to learn in order to produce a good book on Furaha. Here they are again, with some comments:

* Photoshop: I use it regularly now, and am getting better, but still haven't really used it to paint.

* Blender: Nothing yet...

* Indesign: Yes! I am getting the hang of it.

* More species: Yes, but nothing detailed

* Cladograms: No, and at present they do not strike me as very useful.

* Textures: Yes! The astronomy page is proof of that.

And of course there are some things I did not foresee one year ago:

* Interesting contacts with several people, not just in the comments, but behind the scenes as well.

* Working on the blog takes away time from working on Furaha; hmmm...

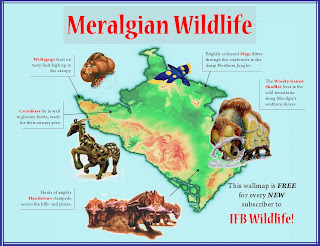

To finish off and to celebrate, I will throw in a few images. The image at the top of this post was made as an experiment for a forum heavy on map making. Just for fun.

And some more:

Sunday, 5 April 2009

Epona I

Over the last few weeks I have asked for other projects dealing with fictional biology. One project wasn't mentioned much, possibly because most readers interested in this kind of thing know of it already, and assumed others did as well. I am talking about the 'Epona project'. At the time, and this is about 1994, it was without a doubt the largest project of its kind, involving the most people. That may no longer be the case, but what many people may not know is that the little that can be found on the Internet only hints at the enormous amount of material accumulated. It did receive its share of the limelight: for instance, there was a session at a World Science Fiction Convention in Glasgow (1994 if I remember correctly), and it made the cover of Analog in November 1996, with a story set in the Epona universe as well as an essay of the scientific backgrounds, by Wolf Read). At present the Epona project seems to be fading out of the public eye, which is a pity.

The project started from a 'Contact Conference', in which one group of people had to come up with alien intelligence, building up the attitude of the aliens from their biological background. Another group played the role of human explorers, and then there is contact. Read more about the Contact conferences here; you will also find some information regarding Epona there.

It grew from there. What made it unique was that it started with a planetary system, devised by Martyn Fogg (who later was kind enough to design Furaha's solar system about one year ago, as an aside for his PhD studies on solar system formation). The planet's geology came next, and the biology built directly on that. I will not mention all names of the 31 people formally involved in the project. You can find their names and much more on the website of the Epona Project. The site looks its age, but is still quite interesting. The thing is that life on land on Epona is only 10 million years old. Oddly, Epona is an old planet, and life there has existed for far longer than it has on Earth. So why hasn't life colonised the land before? Well, it has, and not just once but many times. It died out as many times afterwards.

The reason for this curious phenomenon, which I think is brilliant, is that the planet's system of continental drift has come to a virtual standstill: the planet is losing heat due to old age, and the crust is solidifying. The lack of continuous volcanism ensures that CO2 levels gradually drop, causing the roof of the greenhouse to be opened, so to speak. It gets colder and colder, and life on land is impoverished until it gets to the dead or boring stages.

But every once in a while, say 100 million years, the crust convulses in a gargantuan volcanic shudder, spewing out enormous amounts of CO2. That creates an instant greenhouse effect: the glaciers retreat to the poles, and life crawls onto the beach once more. That is the setting of Epona at present. The last 10 million years have seen an outburst of adaptive radiation of life on land, filling it with an array of forms that at times look maladaptive and at other times look very fit indeed.

It is a pity that the website doesn't show you much of the wildlife that was devised there. Luckily, more can be found on the site of Steven Hanly, who, along with Wolf Read, did many illustrations. I will show a few here, with his permission (there are more on his site!). Looking at them now make you realise the enormous strides computer graphics has made in the last 15 years. The images on Steven's site date from that period, and were among the best that a nonprofessional could then hope to achieve.

So that's Epona. I do have more material on Epona's lifeforms, and will perhaps show some of it here later. But not everything about Epona is in the past. Together with Steven Hanly I have been trying to see whether we could produce some new images of Epona. Here is a test render done in Vue Infinite. It doesn't show many different species yet, but it is a beginning...

Cover of Analog, November 1996.

The animal flying in the foreground is an uther, Epona's sophont.

The animal flying in the foreground is an uther, Epona's sophont.

The project started from a 'Contact Conference', in which one group of people had to come up with alien intelligence, building up the attitude of the aliens from their biological background. Another group played the role of human explorers, and then there is contact. Read more about the Contact conferences here; you will also find some information regarding Epona there.

It grew from there. What made it unique was that it started with a planetary system, devised by Martyn Fogg (who later was kind enough to design Furaha's solar system about one year ago, as an aside for his PhD studies on solar system formation). The planet's geology came next, and the biology built directly on that. I will not mention all names of the 31 people formally involved in the project. You can find their names and much more on the website of the Epona Project. The site looks its age, but is still quite interesting. The thing is that life on land on Epona is only 10 million years old. Oddly, Epona is an old planet, and life there has existed for far longer than it has on Earth. So why hasn't life colonised the land before? Well, it has, and not just once but many times. It died out as many times afterwards.

The reason for this curious phenomenon, which I think is brilliant, is that the planet's system of continental drift has come to a virtual standstill: the planet is losing heat due to old age, and the crust is solidifying. The lack of continuous volcanism ensures that CO2 levels gradually drop, causing the roof of the greenhouse to be opened, so to speak. It gets colder and colder, and life on land is impoverished until it gets to the dead or boring stages.

But every once in a while, say 100 million years, the crust convulses in a gargantuan volcanic shudder, spewing out enormous amounts of CO2. That creates an instant greenhouse effect: the glaciers retreat to the poles, and life crawls onto the beach once more. That is the setting of Epona at present. The last 10 million years have seen an outburst of adaptive radiation of life on land, filling it with an array of forms that at times look maladaptive and at other times look very fit indeed.

It is a pity that the website doesn't show you much of the wildlife that was devised there. Luckily, more can be found on the site of Steven Hanly, who, along with Wolf Read, did many illustrations. I will show a few here, with his permission (there are more on his site!). Looking at them now make you realise the enormous strides computer graphics has made in the last 15 years. The images on Steven's site date from that period, and were among the best that a nonprofessional could then hope to achieve.

Next, a single pagoda tree. Note that is has a fairly simple build. Life hasn't evolved anything like wood yet, so the stems are herbaceous in nature.

So that's Epona. I do have more material on Epona's lifeforms, and will perhaps show some of it here later. But not everything about Epona is in the past. Together with Steven Hanly I have been trying to see whether we could produce some new images of Epona. Here is a test render done in Vue Infinite. It doesn't show many different species yet, but it is a beginning...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)